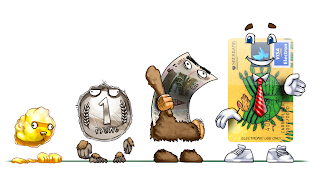

The range of commodities used over time as money is

very wide; it includes cattle, grain, knives, spades, shells, beads, bronze,

silver, and gold. The oldest recorded use of money dates back 4,500 years to

ancient Mesopotamia, now part of Iraq. About 3,500 years ago, cowrie shells

from the Indian Ocean were used as a means of payment in China. Passages in the

Bible indicate that silver was used as a means of payment in the time of Genesis.The first coins--lumps of "electrum," a natural mixture

of gold and silver--were introduced in Asia Minor in the seventh century B.C.

in Lydia, now part of Turkey.

Driving the evolution of money, from the earliest

emergence of commodity money, has been the desire to increase the efficiency of

carrying out exchanges. In the absence of money, trade is accomplished by

barter, the direct exchange of commodities or services to the mutual advantage

of both parties. Such exchanges require a double coincidence of wants or

multiple trades. If I have apples and want grain, I have to find someone who

has grain and wants apples. Alternatively, I can engage in a series of

intermediate trades that ultimately result in the exchange of apples for grain.

In primitive societies with a small range of goods, barter can work well

enough, but as the range of goods expands, barter becomes increasingly

inconvenient and costly.

Several considerations have affected the evolution of

commodity money itself--from cattle and grain toward shells and then bronze and

ultimately to silver and gold. Commodities are useful as a means of payment and

store of value if they were are less bulky in relation to their value, more

durable, more homogeneous, and more easily verified as to their worth than

other commodities. These considerations favored the use of the precious metals,

for example, over cattle and grain, encouraged the use of gold and silver

rather than bronze and copper, and further affected the way that silver and

gold were used as money over time. Early commodity money, for example, was

weighed, not counted, including the early uses of silver and gold. The

introduction of coins that were stamped with their weight and purity allowed

money to be counted and again reduced the costs associated with making

transactions. Silver became the dominant money throughout medieval times into

the modern era. Relative to silver, copper was too heavy and gold was too light

when cast into coins of a size and weight convenient for transactions.

The next important evolution was the introduction of

"representative" paper money. Warehouses accepted deposits of silver

and gold and issued paper receipts. These paper receipts in turn began to

circulate as money, used as a means of payment and held as a store of value.

The paper was fully backed by the precious metals in the warehouse. Once again,

efficiency was enhanced by the convenience of carrying paper money as opposed

to the bulkier silver or gold coins.

Owners of the warehouses soon learned that the holders

of the paper receipts would not simultaneously redeem the gold deposited with

them. The warehouses could therefore lend the gold--in turn, often converted

into paper notes--holding a reserve of gold that allowed them to meet the

normal demands for redemption. This is the beginning of fractional reserve

banking.

Seventeenth-century English goldsmiths are usually

credited with this transition to modern banking, though the first paper money

was introduced in China in the seventh century, a thousand years before the

practice became widespread in Europe. Paper notes and early banking were

introduced in Europe in medieval times and further advanced by the great

banking families of the Renaissance. The spread of paper notes and fractional

reserve banking opened up the potential for credit expansion to support

economic development but also introduced the possibility of runs and liquidity

crises as well as the risk of insolvency through the credit risk associated

with the lending.

In the nineteenth century, many countries were on a

bimetallic standard, allowing the minting of both gold and silver coins. But by

late in that century, many countries had moved to the gold standard, and

currency and bank reserves were backed exclusively by gold. Barry Eichengreen

(1996) describes the gold standard as "one of the great monetary accidents

of modern times," owing to England's "accidental adoption" of a

de facto gold standard in 1717. Sir Isaac Newton was master of the mint at the

time and, according to Eichengreen, set too low a price for silver in terms of

gold, inadvertently causing silver coins to mostly disappear from circulation.

As Britain emerged as the world's leading financial and commercial power, the

gold standard became the logical choice for many other countries that sought to

trade with and borrow from, or emulate, England, replacing silver or bimetallic

standards.

England officially adopted the gold standard in 1816.

The United States moved to a de facto gold standard in 1873 and officially

adopted the gold standard in 1900. The international gold standard refers to

the period from the 1870s to World War I, during which time the major trading

countries were simultaneously on the gold standard. Though many countries went

off the gold standard during World War I, some returned to a form of gold

standard in the 1920s. The final blow to the gold standard was the Great

Depression, by the end of which the gold standard was history.

Eichengreen argues that the emergence of the gold

standard reflected the specific historical conditions of the time. First,

governments attached a high priority to currency and exchange rate stability.

Second, they sought a monetary regime that limited the ability of government to

manipulate the money supply or otherwise make policy on the basis of other

considerations. But by World War I, economic and political modernization was

undermining the support for the gold standard. Fractional reserve banking,

according to Eichengreen, "exposed the gold standard's Achilles'

heel." The threat and, indeed, reality of bank runs created a

vulnerability for the financial system and encouraged governments to seek a

lender of last resort to provide liquidity at times of distress. Such

intervention was, however, inconsistent with the gold standard.

The international gold standard involved adherence to

certain "rules of the game." First, the national unit of currency had

to be defined in terms of a certain quantity of gold. Second, central banks had

to commit to buy and sell gold at that price. Third, gold could be freely

coined, such coins represented a significant part of the money in circulation,

and other forms of money were convertible into gold at a fixed price on demand.

Fourth, gold could be freely imported and exported.

With the collapse of the gold standard, countries

moved to fiat money systems. Fiat money is inconvertible, meaning that it is

not convertible into nor backed by any commodity. It serves as legal tender by

decree, or fiat, of the government. Its value is based on trust--specifically

that others will accept it in payment for goods and services and that its value

will remain relatively stable. This trust is based, in part, on laws that make

the fiat money "legal tender" in the payment of taxes and, in the

United States, also in the payment of private debts.

Fiat money consists of both paper currency and metal

coins the face value of which exceeds the value of the metal content of the

coins. The need to finance wars encouraged early efforts by governments to

issue fiat money. Early examples include the continentals issued by the

American government during the Revolutionary War, assignats issued during the

French Revolution, and the greenbacks issued during the Civil War. Most such

issues of fiat money were followed by severe increases in prices, as

governments tapped to an ever greater degree the easiest--in some cases perhaps

the only--source of revenue. These experiences highlight the importance of

control of the money supply for achieving price stability.

Today, money consists of currency, coin, and

transactions deposits (that is, checking accounts) at depository institutions,

including, in the United States, commercial banks, thrift institutions, and

credit unions.It is not clear when the first check was written.

The earliest evidence of deposits that might be subject to checks is from

medieval Italy and Catalonia. But at that time, the depositor had to appear in

person to withdraw funds or to transfer them to the account of another

customer. Checks did not come into widespread use until the early sixteenth

century in Holland and until the late eighteenth century in England.

The payment system has evolved further in recent

decades with the spread of credit cards and then debit cards. Credit cards

allow consumers to purchase all kinds of goods "on credit," making

payment to the credit-card company for a collection of purchases later by

check. In effect, the use of credit cards separates the purchase of goods from

the ultimate settlement but increases the efficiency of exchange. Debit cards

allow the consumer to make a purchase from a checking account through an

electronic instruction to debit the account instead of by writing a check,

another advance in efficiency.

Even more recently, electronic money has been

introduced, still perhaps more in concept than in practice, at least in the

United States. I will return to the role of electronic money today and the

potential for the spread of electronic money in the future.

Home page.

Home page.

No comments:

Post a Comment